The Decision Space of the Game Monopoly

by Jim D’Ambrosia

Introduction

There’s been a meme going around about the differences between the European and American badgers. I generated some AI pictures and went from a warm cozy feeling to breaking out in a cold sweat in five seconds. I’m not sure I would say that boardgames are exactly like badgers, but there are some who would make just this analogy between the civilized Eurogames of our millennium and the old classic, Monopoly. Although, sure, the game differences have much less to do with nationality and everything to do with decades of evolving game design – Monopoly was released in 1935, and even then it was based on “The Landlord’s Game” from 1903.)

Monopoly currently has a firm reputation as a game that is very much not-the-best. I’m not about to fight anybody on that, but even so, the game does have some decisions in it that are very interesting from a probabilistic/mathematical standpoint. I’ve been listening to this podcast called “Decision Space”, where they discuss qualitative and quantitative decision-making aspects of various cool board games. I am assuming that the good hosts have way too much sense and too little time to spend laying into Monopoly, so I’ll do it myself.

A competitive game of Monopoly naturally breaks into three phases. The boundaries aren’t firm, but you will always go through these stages:

Property acquisition

Trading

Execution/denouement

Each stage has its own distinct decisions to make.

For everything that follows, I’m going to assume that you’re playing with more than two players. The two-player game is much different, and it has fewer, less-interesting decisions, which would surely take us in the wrong direction.

Stage I: Property Acquisition

This is the part of the game where you roll around the board, passing Go and stuff, and most importantly, buying property.

And right off the bat, we meet the first great (but not greatest) practical joke the designer(s) played on us. In this stage, there are no decisions to make! At least, not meaningful ones. At least, not if you want to win. Sure, winning isn’t everything, but if you’re not into winning – and honestly, that’s perfectly acceptable – you can probably find a more fun game to not win at.

Movement in Monopoly is completely deterministic. Roll the dice, move that many spaces. Maybe go to Jail. No decisions here.

Your two categories of decisions:

i) Do you buy a property that you land on? And … the one and only strategy is: you land on a property, you buy it. It’s that simple. Doesn’t matter who owns the other properties in the set.

There’s a bit of a possible complication here if you don’t have enough money to buy. In this case, you mortgage properties to raise the needed funds, if you can possibly do so.

And ok, also in this case, there is a possibly interesting decision of which properties to mortgage. By and large, mortgage the ones you are least likely to trade, and/or the ones least likely to be landed on.

ii) If you go to Jail, do you bust your way out, or try to wait for doubles? Answer: since you are trying to accumulate as much property as possible, you drop the $50 and flee.

So, yeah, chuck dice, move your token around the board, exchange some paper for twenty minutes or so. Good stuff.

Stage II: Trading

There’s no reason to wait until all or most properties are bought before you start wheeling and dealing, but that’s how it’s done in most of the games I’ve played.

This isn’t always realized, but in a multi-player game, the winner of the game is virtually never determined by what happens during Stage I. The only way this happens is if exactly one player gets a complete monopoly (color set of properties) and also gets at least one of each property in all the other color sets. It’s very unlikely.

And here we get to the greatest design joke of all. If no player has a complete color set, and nobody trades, then the game goes on forever. Sweet! This is actually pretty funny, in that the official rules barely mention trading, which is mostly an emergent cultural tradition. You can imagine a horror story about some poor college kids who had never played before, and one summer went off to a cabin in the woods and found the game in a closet. They were still playing six years later when some hikers stumbled in and pointed out that maybe exchanging Illinois Avenue for St. James Place could speed things along.

The good news, if you’re still with me, is that in almost all cases of how the properties fall out, there is a game to be had, and each player has a definite possibility of winning. Not always an equal chance, but usually a decent one at least. If one player has a monopoly and you and the third player don’t, you can make a deal with that third player. It doesn’t matter if player 3 has like a million dollars and most of all the properties, while you have like $12 and the worst of the rest. If they are too important to trade with you, they will suffer the same fate as you, except their suffocating death will be a bit more drawn-out. You can go ahead and congratulate them on this.

What’s cool is that you can trade with your rich fellow loser-to-be on an even basis and make up a lot of ground.

If both players have complete sets and you are feeling left out in the cold, well, yeah. You are up against it, but aren’t out of it. One player will be stronger than the other, and at some point, the weaker will be up for a deal. But you might need to talk them into it before you get knocked out of the game.

Trading is by far the most interesting source of decisions you will make in the game. You will want to consider the entire state of the game:

the properties you own

the properties each other player owns

the board location of every player

the amount of money each player has

the number of houses available in the supply

The key considerations are how quickly you will be able to build out your properties versus the same for your opponents, compared to how soon you expect them to land on yours and vice-versa. So you will also want to know the basic probability distribution of throws of a pair of dice (7=most likely; 2 and 12 the least). It’s nice if you have a breakdown of the most frequently visited color sets in the game handy, but you at least want to know that by and large the Oranges (New York and friends) make the best set to get, as a combination of visits and punishing power, followed by some order of the Reds (Illinois), the Yellows (Marvin & his gardens) and Dark Blues (everybody’s favorite, Boardwalk). There are all kinds of websites out there showing you probabilities and ROIs and whatnot, and far be it for me to discourage anyone from being interested in raw numbers, but cash-on-hand and board position outweigh how good a property is in the abstract.

You’ve got a number of levers with which to calibrate your trades. The tangible assets, properties and money, in the trade are a given, but there are all sorts of intangible instruments that you can use – at least if you are not playing under tournament rules. You can trade off free passes, for example. Give me Boardwalk for my Virginia Avenue, and I won’t charge you the next four times you land on my Dark Blues. I’ll give you that lousy Mediterranean Avenue, but I’ll sweeten the deal by agreeing to pay you $200 each time I land on it. If the players are good at evaluating positions and states, you can get reasonably close to making fair trades. Not sure how fun it is to give everyone else the same chances of winning as you, but it’s possible.

If you want to get technical about it, the branching factor at this point is enormous. You have choices as to which properties to trade with which players (and trades can involve more than two players), in addition to how much money will change hands.

There’s a lot more to be said here, but now we’re getting into legit strategy instead of feeling out the decision space. I would guess that trading makes up maybe 80% of the interesting decisions of the game, and I truly find these decisions to be involving.

Stage III: Execution/denouement

Hopefully you’ve done some nifty trading, and now have a color set you can develop. Welcome to another challenging set of decisions. You may have a choice of sets to build on, but whether you do or not, timing your builds is critical. The key point here is that if you run out of money, you sell your improvements (houses/hotels) at a 50% discount, so there is a steep penalty if you build and don’t collect before getting slammed by landing on your opponents’ properties.

Ideally, you’d be totally loaded and can hotel it up and still have enough reserves to withstand landing on other players’ hotels a few times. But that never happens. There is always going to be a gamble – a big gamble – and a decision of how much money to put into development and how much to leave in reserve.

It’s not easy. You have to play aggressively to win, but you have to take measured risks. Again, the whole game state is involved. Repeating myself, this includes:

the properties you own

the properties each other player owns

the board location of every player

the amount of money each player has (actually, I don’t know how much this matters)

the number of houses available in the supply

The availability of houses is a less-understood factor. Unlike with money, the housing (and hotelling) supply is strictly limited. And adding to that, it’s a rule that you have to build out four houses on each property in a set before upgrading to hotels. So you can block opponents from building by acquiring houses and not relinquishing them.

The branching factor here is reasonably large, but not insane. You have to determine when to buy, how much to spend, and where to place the improvements.

The good news is that you will most likely have an ongoing series of these fun decisions, as you collect money (hopefully) or lose money but still have chances to rebuild (also hopefully).

The bad news is that while there may still be decisions left during the course of the game, they aren’t fun no more.

If you’re lucky, you’ll be winning. Any decisions from here on out are easy and make themselves, and can you get satisfaction (hopefully a grim kind) from squeezing the life out of your fellow players who had kindly agreed to join you for this game (or “game”, if you prefer). If you are less lucky, you will get that said life squeezed out of YOU, but not before you get to make some excruciating choices while your life ebbs away. Namely, which improvements to sell off, and then which properties to mortgage.

Ok, to be fair, I was a bit hasty in writing off your chances and your life. Apologies. The dice are random, and it is very possible to recover, and depending on how other players are doing, it may be worth their while to toss you some money for some worthless property and keep you in the game. So, the death spiral isn’t irreversible, but still, if you have N players, it’s a guarantee that N-1 of them are going down. Enjoy!

Might as well mention the punch-line of the final joke, which won’t surprise anyone. For all the depth of those decisions that I claimed were interesting, in the end, luck plays a major role. In a sense, this can be inevitable. If you’re playing with others who are skilled at evaluating the board and making those decisions, the trades will be calibrated to be generally equitable among the participants. All other things being even, the dice will call the shots from here on out. Don’t get me wrong; I don’t personally consider this game to be a luck-fest. The better strategies will win out, but it will take more than a few plays. There aren’t enough rolls to even things out in the critical period of a single game.

Let’s quickly recap:

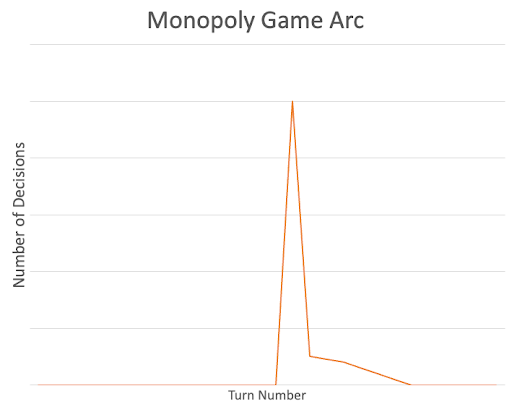

The first half of the game, you make no decisions.

You then have a few critical decisions with an awful lot of options. By and large, these decisions along with all subsequent dice rolls will determine the game.

You then have a few followup decisions on when and where to build improvements …

… followed by a grim march to a somewhat random ending, either heartlessly taking money from the other players, or selling at a loss what you’ve worked your whole game life to build.

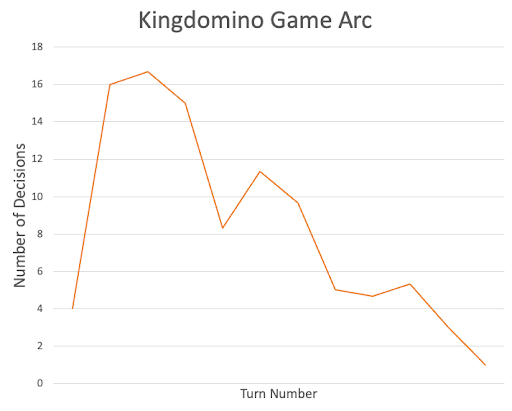

You get the idea, but let’s go ahead and contrast this with a nice, well-behaved Eurogame such as the excellent Kingdomino. In that game, each turn you choose a tile, with 1-4 options to choose from, and then you have from zero to seventeen or so meaningful choices of where to put the tile. I used the super-scientific technique of playing one (1) four-handed game and manually counting all the possible placements, but these minimal observations are in line with the much more systematic and interesting investigation found here: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328308743_Monte_Carlo_Methods_for_the_Game_Kingdomino. I did not put the two lines on the same chart, since that peak decision count for Monopoly can reach into the hundreds of thousands and beyond.

Good times.

Full disclosure: I have been playing this game (or “game”, if you will), for over 45 years, and still enjoy it. I totally get why many disagree.

Thought Question

As I’ve said, I really do think the trading, and the timing on property improvements, make for some interesting decisions – and decisions that I’m not sure I’ve really seen in other games. At least, not that I can think of. I’ll have to consider this some more. Many of you will disagree, and think those decisions suck along with the rest of the game. But now I am wondering if it’s possible to extract those determinations into a different, better game. After all, one of the disappointments of Monopoly for me is that the fun part comes and goes quickly. It’s too small a portion of the game. I know you can speed up the game – heck, just deal out the property cards in the beginning – but there’s possibly, maybe, a way to design something much better, that still gives you those sorts of choices? I wonder.

Editorial Comment

Hopefully I’ve done a good job of being fair to the game, and pointing out many (but not all) of its significant flaws. If you’re willing to give the decisions in the game some credit, it might be worth considering it in historical context. There was absolutely nothing on the mass market like Monopoly when it came out. Heck, its forbear, The Landlord’s Game, was designed in 1903 before the mathematical techniques to analyze it were developed. Andrey Markov didn’t publish his first paper on Markov Chains until three years later, in 1906. Even then, you would have to be some kind of numbers masochist to create and manipulate by hand the 40x40 matrix needed to determine the frequency probabilities.

In terms of pure board games, you had slim pickings to choose from in 1935. You could play the hot new Eurogame import, Sorry!. If you wanted to play Scrabble or Clue then you had to sit around for a dozen years waiting for those to be invented. Borrrrrrrring. Monopoly brought to the table (so to speak) a quantitative depth that was unprecedented.

Further Reading

1000 Ways to Win Monopoly Games. Jay Walker and Jeff Lehman, 1975.

So when I was ten, a babysitter brought this over to our house one day, and I had time to read a few chapters. It was literally the most amazing book I had ever read to that point in my life, and opened my eyes to the possibilities of mathematical analysis. Sadly, the babysitter took it with her when she left, and she moved, and I never could find it in a library, and had to wait for the rise of the Internet to locate it again. The book still holds up, mostly, although some no-fun suits have outlawed cool things like trading options and such for tournament play. One crazy fact is that the authors, who were undergraduates at Cornell University at the time, went on to pull wacky stunts like founding priceline.com and becoming the president of Cornell. If you enjoy this game, I’d heartily recommend reading it. Lehman has posted the book on his website: http://www.lehman-intl.com/jeffreylehman/1000-ways-to-win-monopoly.html .

The Monopolists: Obsession, Fury, and the Scandal Behind the World's Favorite Board Game. Mary Pilon, 2015.

This book covers the early developments of the game, especially how it was derived from The Landlord’s Game. Which was a fact that Parker Brothers was verrrrrrrrrry interested in you not knowing about – and I didn’t know about it myself until I read this book. I am completely fascinated by Lizzie Magie and the early history of the game.

Jim D’Ambrosia, © 2022